With Covid-19 risks looming large, wiiw sees no quick recovery in sight

According to new projections released on November 12 by the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw), the recovery of Eastern European economies will be sluggish and will depend on success in containing the Covid-19 pandemic without resort to lengthy lockdowns, as well as on the continuation of government support measures.

In its new economic projections for Central, East and Southeast Europe (CESEE) in 2020-2022, wiiw says that while most of CESEE withstood the first wave of the pandemic better than Western Europe, many economies in the region still suffered badly – especially those reliant on tourism (Croatia and Montenegro) and those with a high dependence on foreign trade (the smaller Visegrád countries and Slovenia).

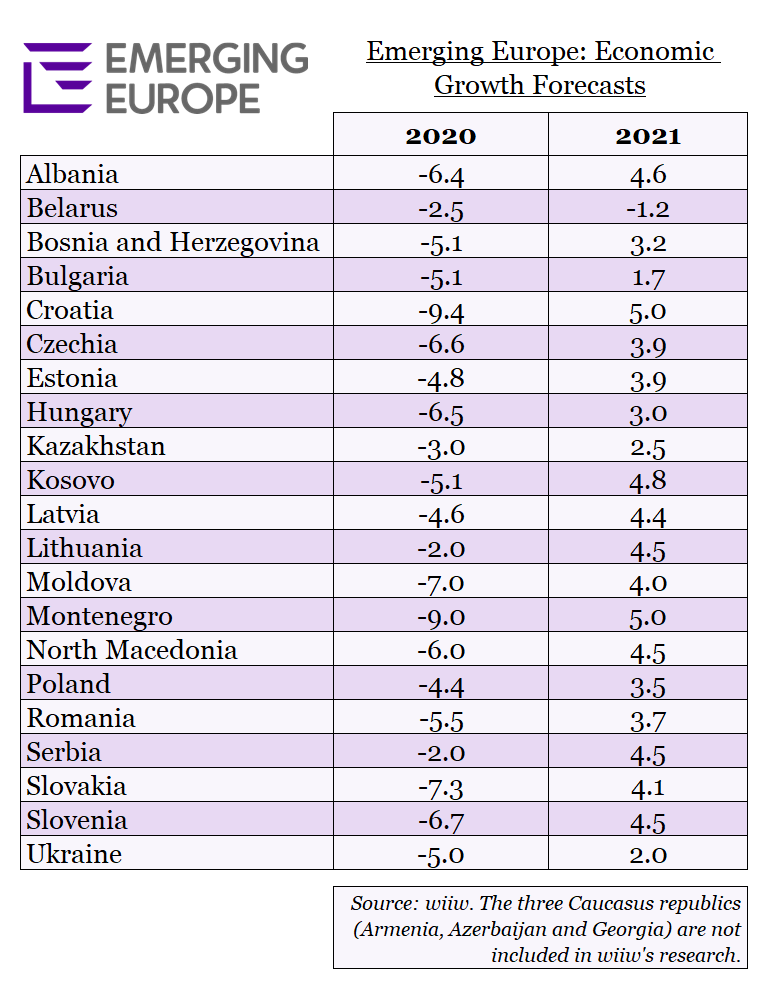

Indeed, wiiw forecasts Croatia and Montenegro to see the region’s biggest falls in GDP in 2020, of 9.4 per cent and 9.0 per cent respectively.

The fiscal response

As in Western Europe, CESEE governments have responded with a marked policy relaxation, taking advantage of the fiscal and monetary space available. Policy rates have been cut sharply, contributing to currency depreciations (of more than 20 per cent since the start of the year, in some cases) which mitigated the impact of the external demand shock. Besides, a wide range of government support measures has been adopted, including most notably subsidised short-time work schemes, which saved many jobs and have limited the rise in unemployment, at least so far.

Partly due to the policy stimuli enacted (especially on the fiscal side), CESEE economies rebounded strongly in the third quarter. Retail trade benefited from purchases delayed during the lockdown, and international production chains largely resumed their operation. However, the pre-crisis levels of economic activity have not been reached. Besides, the second wave of the pandemic, which started in many CESEE countries in September, has given rise to concerns over the ability of healthcare systems to cope with the soaring numbers of hospitalisations. This has already prompted a renewed full lockdown in Czechia and partial lockdowns in Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia, while other countries may soon follow suit, making double-dip recessions (on a quarterly basis) almost unavoidable this year. The region as a whole will post a full-year contraction of 4.5 per cent for 2020, with risks to this estimate now weighted quite heavily on the downside.

As a result, wiiw says that the medium-term economic prospects for CESEE are surrounded by enormous uncertainty.

“In our baseline scenario, which assumes that an effective vaccine/treatment for Covid-19 will contain the pandemic without the need for lengthy lockdowns, CESEE economies are projected to grow on average by 3.1 per cent in 2021 and 3.3 per cent in 2022,” says wiiw’s report. “Across the CESEE countries, the economies of Croatia and Montenegro are expected to grow by five per cent next year, as the tourism industry partly recovers the losses incurred this year.

By contrast, in Russia and Kazakhstan, growth will barely exceed 2.5 per cent, as oil prices are unlikely to recover substantially from their current levels and oil production will still be constrained by the OPEC+ quotas. Even in this benign scenario, the 2019 levels of economic activity in CESEE countries will not be reached before 2022 (except in Lithuania, Serbia and Turkey), and Belarus will record another year of recession due to the fallout from the current political crisis.”

The Vienna Institute warns that any further spread of the virus would not only necessitate further lockdowns (in both CESEE and Western Europe), with direct contractionary effects for the economies of the countries involved, but would also affect the demand for durable consumer and investment goods, due to the high level of uncertainty.

Furthermore, the pandemic – even if successfully contained – may leave a lasting legacy in the form of depressed demand for many services, such as aviation, hospitality and recreation, making businesses in those sectors dependent on continued government support. “The need for such support will clearly increase in the event of renewed lockdowns,” say the economists at wiiw.

In those CEE countries which are members of the European Union, continued government support should be less of a problem: they have generally enough fiscal space and will benefit from various EU transfers, including the Next Generation EU funds, which in some cases (such as Croatia and Bulgaria) will exceed three per cent of GDP per year.

However, such government support may be more problematic in some Western Balkan countries, as well as Ukraine and Moldova, which have high public debt-to-GDP ratios and/or are highly dependent on external assistance.

State intervention

The Vienna Institute’s forecast come just a couple of days after the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) published a new report that looks at the tough choices the region’s economies face in determining whether an increased role for government will have positive or negative long-term consequences.

The report notes that Covid-19 has sparked calls for more state intervention, in her foreword to the publication, called The State Strikes Back, EBRD Chief Economist Beata Javorcik says the ability of emerging economies to deliver successful policies against a backdrop of increasing state influence depends crucially on the quality of institutions and public governance.

“The economies of the EBRD regions stand at a crossroads, with decisions on policies and institutions that are taken now potentially determining their paths for decades to come. The current period of crisis and upheaval triggered by the global pandemic represents a valuable opportunity to lay the foundations for a wealthier, fairer and greener future,” says Javorcik.

The new report notes that state-owned enterprises continue to play an important role in the EBRD regions, providing almost half of all public-sector employment. It says they can be a stabilising force for economies, providing employment during downturns and in disadvantaged regions.

However, governments are not particularly effective in the management of state enterprises, which are likely to be less innovative than their private-sector counterparts.

State-owned banks have grown in importance across the EBRD regions since the mid-2000s and become major competitors to the private sector, because many have less stringent lending standards, lower net interest rate margins and a higher tolerance of non-performing loans.

A willingness of state banks to assume risks can help soften the impact of economic shocks. On the downside, however, firms that borrow from the state financial sector tend to be less innovative and show weaker productivity growth.

This is partly a reflection of the fact that state-owned banks may be more susceptible to political interference in their lending decisions and so channel finance away from more productive firms.

The report also says that EBRD economies are falling behind in the enforcement of policies that help reduce carbon emissions, in the wake of the 2015 Paris Agreement.

(News source: emerging-europe.com)